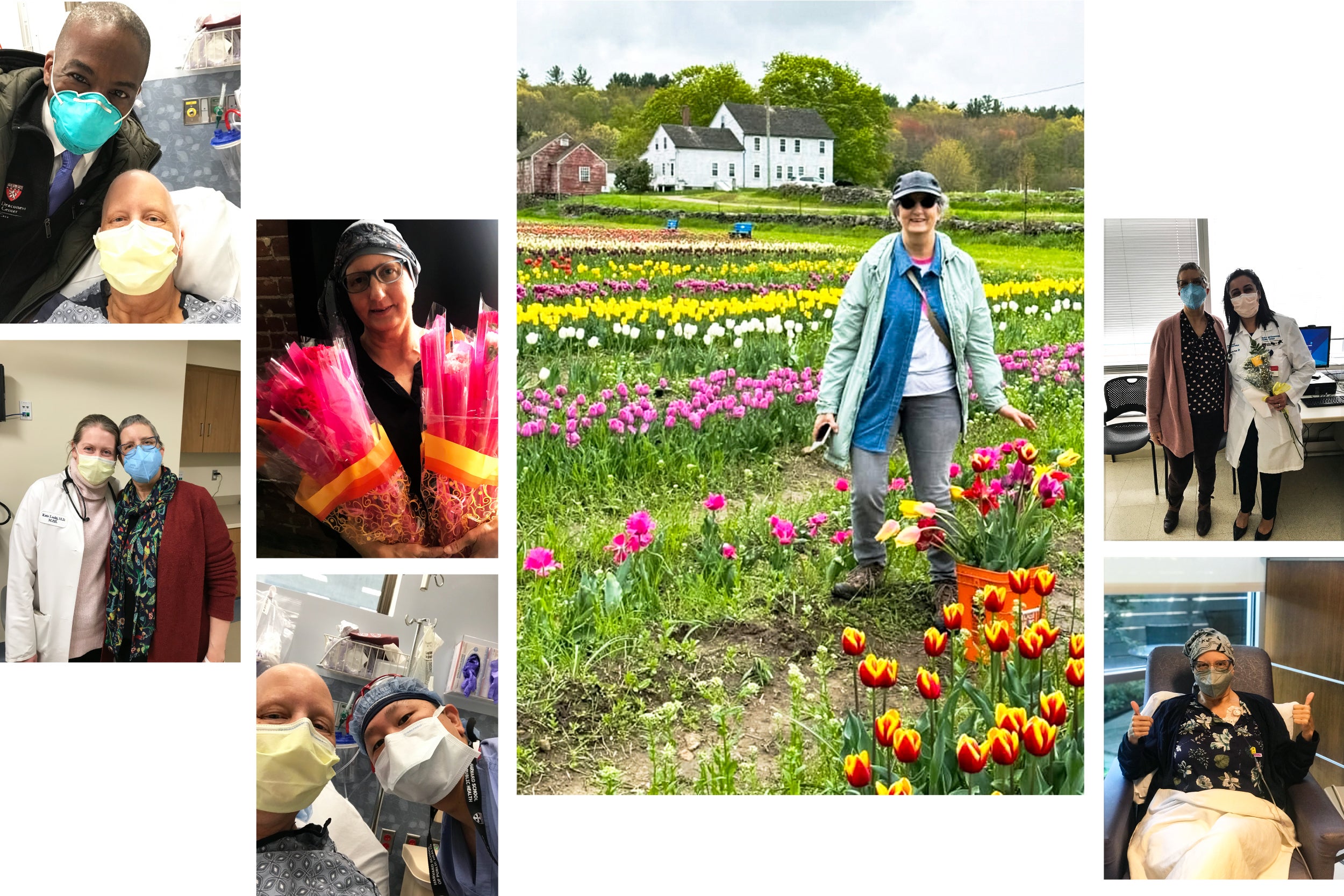

Bobbie Collins with flowers for her healthcare teams at different milestones during her treatment and pictured with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center staffers including Ted James (far left top), Kathleen Leahy (far left bottom), Bernard Lee (middle left bottom), and Aarti Asnani (top far right). At bottom far right Collins is shown 12 weeks into treatment before her final chemo-immunotherapy session.

Health

Gift of tulips: Surviving breast cancer

Tracing ups, downs of treatment; loss of sister; gratitude for friends, family — and power of academic medicine

I was home less than an hour after having lumpectomy surgery for triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) when I got a call from my niece’s husband telling me my eldest sister Christina Dobbyn Wood had died.

Chrissy had succumbed, at age 75, to triple negative inflammatory breast cancer, a rare subtype that propagates rapidly. The date was Oct. 5, 2022, only 16 months after she’d first learned of her illness. At the time of her diagnosis, Chrissy was stage 4 metastatic, meaning it had already spread significantly in her body. She told me that the average life expectancy for women with this cancer was two years.

Grief eclipsed the relief I felt at having had successful surgery. What’s more, I found myself unable to fully enjoy the even better news that arrived soon after: Following six months of pre-surgery chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy there was no evidence of disease in my body. After sustaining each other through our grueling treatments, there was no Chrissy to share the good news with.

She was a role model of grace and acceptance for me. So much so, that when I was first diagnosed in March 2022, after the shock of my diagnosis wore off, the most powerful emotional response I felt was profound gratitude, which only continued to deepen throughout my treatment.

For sure, I was, and am, thankful for my husband, Gary DelPonte, who cared for me steadfastly — by cooking, cleaning, driving, sharing emotional strength; for loved ones near and far, who lent a shoulder to lean on or gave me cheer to buoy my spirits; for a supportive workplace with officemates who were understanding and gave me courage; and my employer and my union with their great benefits and programs.

My experiences also deepened my appreciation for academic medicine’s mission of training doctors and scientists, as well as its essential roles in the development of new treatments and drugs and the delivery of compassionate, expert healthcare. I already had some sense of all this, having worked at Harvard Medical School in the Office of Communications and External Relations for more than eight years, sharing news stories and reports about HMS’s amazing students and remarkable faculty. Now I could speak from experience.

Both Chrissy and I were able to reap the benefits of care from teaching hospitals and medical schools with their research labs and affiliated faculty clinicians. We both received therapies that had their beginnings in the lab where researchers elucidated the structure and workings of cells, tumors, genes, and systems in the human body, and clinicians studied therapies being developed to manage symptoms and cure disease.

I also found it joyful and hopeful having medical students, undergraduate students from Boston-area community colleges and universities, and residents and interns be a part of my treatment teams — I asked about and encouraged their educational and career plans whenever I met them.

Family history

Our family knows how far the science has come. About 17 years ago, my sister-in-law Susan Kropp Collins, who was of Ashkenazi Jewish descent and had a BRCA1 gene inherited mutation, discovered a lump. She received chemotherapy, but immunotherapy was not available for breast cancer then.

After the later stage breast cancer initially responded to chemo by seemingly disappearing, it resurged, and she died within weeks, at age 40, in December 2007. My paternal aunt Joanne McDonald also died in 1982 at 45 from breast cancer. Both had young children. More recently and thankfully, my paternal cousin Kitty Senn was successfully treated for stage 1B non-genetic TNBC in 2020.

While Chrissy was not a candidate for immunotherapy, I was, and again I am thankful, grateful that pembrolizumab was approved by the FDA as the first immune checkpoint in inhibitor therapy for high risk, early stage TNBC the year prior to my diagnosis.

For almost 15 years, immunotherapy has been a game-changer for people with certain cancers, significantly increasing disease-free survival rates. These drugs have been made possible largely by the work of scientists in academic medicine.

Immunotherapy drugs have been developed based on the patents held on PD-1 pathway and immune checkpoint inhibitors by two HMS scientists: Arlene Sharpe, the Kolokotrones University Professor and head of the Department of Immunology at HMS, and Gordan Freeman, professor of medicine at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Despite not being eligible for immunotherapy, with the care Chrissy received at the Moffitt Cancer Center, a research hospital in Florida, she survived 10 months longer than expected, living as many of those days as she could to the fullest, even realizing a bucket-list wish to fly in a World War I biplane.

While she accepted her illness and future with grace, she was visibly struck to hear about mine.

Her initial words “That’s horrible,” still echo in my ears. The devastating tone of shock in her voice struck a chill in my heart and brought my diagnosis and her terminal reality into stark focus.

Breast cancers are frightfully common — one in eight women will get one.

While my future was far from certain, I began to feel I had excellent odds of a good outcome — and yet more to be thankful for — because I live within an hour of some of the best hospitals in the U.S. and could have my case reviewed and treatment recommended by a Harvard Cancer Collaborative board.

“We’re going for cure,” were the hopeful words I heard from oncologist Kathleen Leahy, instructor in medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, when we reviewed my treatment plan.

And over the next six months, Chrissy was happy to see the positive response I was having to treatment and assured me I would live many more years. After a memorial service for her in Florida in December, which I could not attend because I was going in for daily radiation appointments, her daughter Heidi Dobbyn passed along Chrissy’s wish for me that I not experience survivor guilt.

About breast cancers

TNBC only makes up 10 to 15 percent of breast cancers. It grows and spreads rapidly and has fewer treatment options and worse outcomes than other types of breast cancer. The five-year survival rate is about 77 percent.

Fewer than 5 percent of breast cancers are inflammatory, and the rate of survival at five years is just 19 percent if it has spread distantly in the body.

The question “Why and how did we both get breast cancer — in the same year?” lingers in my mind.

The first part can be answered with another “Why not?” Breast cancers are frightfully common — one in eight women will get one. Men get breast cancer, too, but at a much lower rate, about two in every 100,000 men.

I don’t think we’ll ever know why two postmenopausal maternal half-sisters, who are 16 years apart in age, had different lifestyles, and lived in different states much of their lives, both got such uncommon, aggressive cancers.

The answer, so far, is not genetics, because neither of us tested positive for gene mutations that have been associated with TNBC.

What is known is that women who are younger, whose ethnicity is non-Hispanic Black, or who have a BRCA1 gene mutation are more likely to be diagnosed with TNBC.

Discovering it early

I initially found the 2.1 centimeter lump near the left center of my right breast during a self-exam in late February 2022, just three months after I had gotten a routine mammogram and additional imaging on my right breast because of a calcification in the lower-right portion of that breast, in late November 2021 — the report came back with no evidence of malignancy.

The diagnosis I received four months later was invasive ductal carcinoma, stage 2B, grade 3 TNBC (the most aggressive grade) with questionable, at first, lymph node involvement — ultimately further tests showed the cancer had not spread to the lymphatic system, thankfully.

The successful response I had to four chemotherapy drugs delivered over six months, breast-conserving surgery with sentinel lymph node biopsy, four weeks of radiation (which I received at Rhode Island Hospital, a teaching hospital closer to my home), followed by an additional six months of pembrolizumab means I have a 91 percent, or better, chance of not having a recurrence in five years.

Contributing to academic medicine

Except for heavy fatigue I tolerated treatment with minimal common negative side effects, like nausea, thanks to my clinicians’ symptom management with steroid, anti-nausea, and other medications. But I did experience a serious, uncommon side effect — cardiotoxicity from one of the chemo drugs, doxorubicin hydrochloride, which caused my heart’s left ventricle ejection fraction to drop from a high normal of 74 percent to a below normal 38 percent, a reading that indicates impaired functioning and systolic heart failure.

The condition is being successfully treated, and I have been given an opportunity to contribute to science as a patient. Aarti Asnani, a cardio-oncologist and HMS assistant professor of medicine at Beth Israel, asked me to write a letter of support for a grant application to study the detection and treatment of heart-related conditions that arise before, during, and after cancer treatment and to participate in the study should the grant receive funding.

Thirteen months and three days since I began treatment, I finished with a last dose of pembrolizumab on May 4 and celebrated by showing my gratitude for the office assistants, nurses, nursing assistants, lab techs, pharmacists, interns, and physicians at the cancer center with a gift of tulips. Giving flowers is a tradition that I came up with to mark milestones in my treatment and give thanks to my oncology, breast surgery, plastic surgery, radiation, and cardiology care teams.

It has been a long, difficult road. But I am looking forward to continuing to honor my family members and all those who have been affected by breast cancer, by contributing to science and academic medicine as a patient and as an HMS employee.